Introduction¶

Self is a prototype-based dynamic object-oriented programming language, environment, and virtual machine centered around the principles of simplicity, uniformity, concreteness, and liveness.

Self includes a programming language, a collection of objects defined in the Self language, and a programming environment built in Self for writing Self programs. The language and environment attempt to present objects to the programmer and user in as direct and physical a way as possible. The system uses the prototype-based style of object construction.

The first version of the Self language was designed in 1986 by David Ungar and Randall B. Smith at Xerox PARC. A series of Self implementations and a graphical programming environment were built at Stanford University by Craig Chambers, Urs Hölzle, Ole Agesen, Elgin Lee, Bay-Wei Chang, and David Ungar. The project continued at Sun MIcrosystems Laboratories, where it benefited from the efforts of Randall B. Smith, Mario Wolczko, John Maloney, and Lars Bak. Smith and Ungar jointly led it there. Work on the project officially ceased in 1995

Release 4.0 contained an entirely new user interface and programming environment designed for “serious” programming, enabling the programmer to create and modify objects entirely within the environment, and then save the object into files for distribution purposes. The metaphor used to present an object to the user is that of an outliner, allowing the user to view varying levels of detail. Also included in the environment is a graphical debugger, and tools for navigation through the system.

Self is available for Solaris, Linux and natively on MacOS X under a BSD-like licence; we would be very interested in anyone prepared to make a Windows port.

System Overview¶

This section contains an overview of the system and its implementation; it can be skipped if you wish to get started as quickly as possible.

Although Self runs as a single UNIX [1] process, or a single Macintosh application, it really has two parts: the virtual machine (VM) and the Self world, the collection of Self objects that are the Self prototypes and programs:

The VM executes Self programs specified by objects in the Self world and provides a set of primitives (which are methods written in C++) that can be invoked by Self methods to carry out basic operations like integer arithmetic, object copying, and I/O. The Self world distributed with the VM is a collection of Self objects implementing various traits and prototypes like cloning traits and dictionaries. These objects can be used (or changed) to implement your own programs.

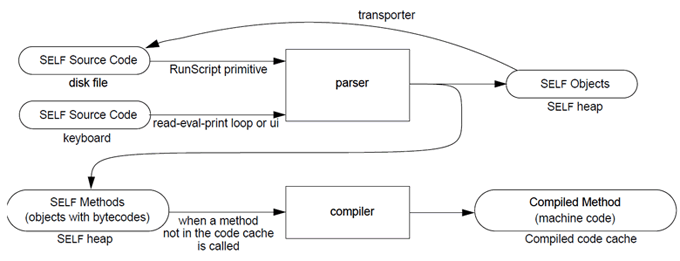

Self programs are translated to machine code in a two-stage process (see Figure 2). Code typed in at the prompt, through the user interface, or read in from a file is parsed into Self objects. Some of these objects are data objects; others are methods. Methods have their own behavior which they represent with bytecodes. The bytecodes are the instructions for a very simple virtual processor that understands instructions like “push receiver” or “send the ‘x’ message.” In fact, Self bytecodes correspond much more closely to source code than, say, Smalltalk-80 bytecodes. (See [CUL89] for a list of the Self byte codes.) The raison d’être of the virtual machine is to pretend that these bytecodes are directly executed by the computer; the programmer can explore the Self world down to the bytecode level, but no further. This pretense ensures that the behavior of a Self program can be understood by looking only at the Self source code.

The second stage of translation is the actual compilation of the bytecodes to machine code. This is how the “execution” of bytecodes is implemented—it is totally invisible on the Self level except for side effects like execution speed and memory usage. The compilation takes place the first time a message is actually sent; thus, the first execution of a program will be slower than subsequent executions.

Actually, this explanation is not entirely accurate: the compiled method is specialized on the type of the receiver. If the same message is later sent to a receiver of different type (e.g., a float instead of an integer), a new compilation takes place. This technique is called customization; see [CU89] for details. Also, the compiled methods are placed into a cache from which they can be flushed for various reasons; therefore, they might be recompiled from time to time. Furthermore, the current version of the compiler will recompile and reoptimize frequently used code, using information gathered at run-time as to how the code is being used; see [HCU91] for details.

Don’t be misled by the term “compiled method” if you are familiar with Smalltalk: in Smalltalk terminology it denotes a method in its bytecode form, but in Self it denotes the native machine code form. In Smalltalk there is only one compiled method per source method, but in Self there may be several different compiled methods for the same source method (because of customization).

Footnotes

| [1] | UNIX is a trademark of AT&T Bell Laboratories. |