Language Reference¶

This chapter specifies Self’s syntax and semantics. An early version of the syntax was presented in the original Self paper by Ungar and Smith [US87] ; this chapter incorporates subsequent changes to the language. The presentation assumes a basic understanding of object-oriented concepts.

The syntax is described using Extended Backus-Naur Form (EBNF). Terminal symbols appear in Courier and are enclosed in single quotes; they should appear in code as written (not including the single quotes). Non-terminal symbols are italicized. The following table describes the metasymbols:

| META-SYMBOL | FUNCTION | DESCRIPTION |

| ( and ) | grouping | used to group syntactic constructions |

| [ and ] | option | encloses an optional construction |

| { and } | repetition | encloses a construction that may be repeated zero or more times |

| | | alternative | separates alternative constructions |

| → | production | separates the left and right hand sides of a production |

A glossary of terms used in this document can be found in Appendix A.

Objects¶

Objects are the fundamental entities in Self; every entity in a Self program is represented by one or more objects. Even control is handled by objects: blocks (§2.1.7) are Self closures used to implement user-defined control structures. An object is composed of a (possibly empty) set of slots and, optionally, code (§2.1.5). A slot is a name-value pair; slots contain references to other objects. When a slot is found during a message lookup (§2.3.6) the object in the slot is evaluated.

Although everything is an object in Self, not all objects serve the same purpose; certain kinds of objects occur frequently enough in specialized roles to merit distinct terminology and syntax. This chapter introduces two kinds of objects, namely data objects (“plain” objects) and the two kinds of objects with code, ordinary methods and block methods.

Syntax¶

Object literals are delimited by parentheses. Within the parentheses, an object description consists of a list of slots delimited by vertical bars (‘|’), followed by the code to be executed when the object is evaluated. For example:

( | slot1. slot2 | ’here is some code’ printLine )

Both the slot list and code are optional: ‘( | | )’ and ‘()’ each denote an empty object. [1]

Block objects are written like other objects, except that square brackets (‘[’ and ‘]’) are used in place of parentheses:

[ | slot1. slot2 | ’here is some code in a block’ printLine ]

A slot list consists of a (possibly empty) sequence of slot descriptors (§2.2) separated by periods. A period at the end of the slot list is optional. [2]

The code for an object is a sequence of expressions (§2.3) separated by periods. A trailing period is optional. Each expression consists of a series of message sends and literals. The last expression in the code for an object may be preceded by the ‘^’ operator (§2.1.8).

Data objects¶

Data objects are objects without code. Data objects can have any number of slots. For example, the object () has no slots (i.e., it’s empty) while the object ( | x = 17. y = 18 | ) has two slots, x and y.

A data object returns itself when evaluated.

The assignment primitive¶

A slot containing the assignment primitive is called an assignment slot (§2.2.2). When an assignment slot is evaluated, the argument to the message is stored in the corresponding data slot (§2.2) in the same object (the slot whose name is the assignment slot’s name minus the trailing colon), and the receiver (§2.3) is returned as the result. (Note: this means that the value of an assignment statement is the left-hand side of the assignment statement, not the right-hand side as it is in Smalltalk, C, and many other languages. This is a potential source of confusion for new Self programmers.)

Objects with code¶

The feature that distinguishes a method object from a data object is that it has code, whereas a data object does not. Evaluating a method object does not simply return the object itself, as with simple data objects; rather, its code is executed and the resulting value is returned.

Code¶

Code is a sequence of expressions (§2.3). These expressions are evaluated in order, and the resulting values are discarded except for that of the final expression, whose value determines the result of evaluating the code.

The actual arguments in a message send are evaluated from left to right before the message is sent. For instance, in the expression:

1 to: 5 \* i By: 2 \* j Do: [\|:k \| k print ]

1 is evaluated first, then 5 * i, then 2 * j, and then [|:k | k print]. Finally, the to:By:Do: message is sent. The associativity and precedence of messages is discussed in section 4.

Methods¶

Ordinary methods (or simply “methods”) are methods that are not embedded in other code. A method can have argument slots (§2.2.3) and/or local slots. An ordinary method always has an implicit parent (§2.2.4) argument slot named self. Ordinary methods are Self’s equivalent of Smalltalk’s methods.

If a slot contains a method, the following steps are performed when the slot is evaluated as the result of a message send:

- The method object is cloned, creating a new method activation object containing slots for the method’s arguments and locals.

- The clone’s self parent slot is initialized to the receiver of the message.

- The clone’s argument slots, if any, are initialized to the values of the corresponding actual arguments.

- The code of the method is executed in the context of this new activation object.

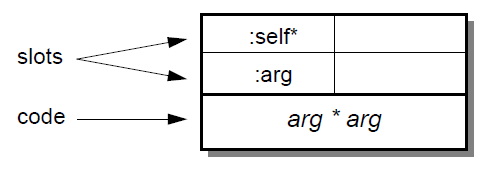

For example, consider the method ( | :arg | arg * arg ):

This method has an argument slot arg and returns the square of its argument.

Blocks¶

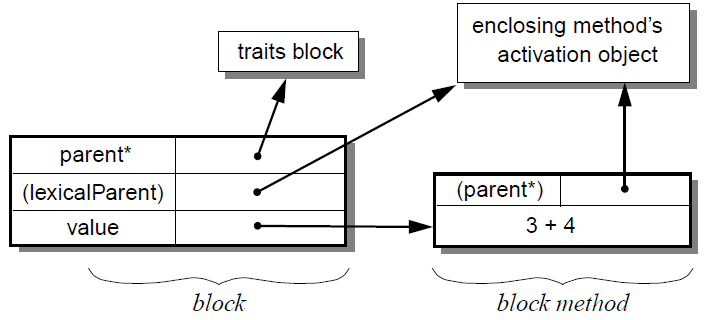

Blocks are Self closures; they are used to implement user-defined control structures. A block literal (delimited by square brackets) defines two objects: the block method object, containing the block’s code, and an enclosing block data object. The block data object contains a parent pointer (pointing to the object containing the shared behavior for block objects) and a slot containing the block method object. Unlike an ordinary method object, the block method object does not contain a self slot. Instead, it has an anonymous parent slot that is initialized to point to the activation object for the lexically enclosing block or method. As a result, implicit-receiver messages (§2.3.4) sent within a block method are lexically scoped. The block method object’s anonymous parent slot is invisible at the Self level and cannot be accessed explicitly.

For example, the block [ 3 + 4 ] looks like: [3]

The block method’s selector is based on the number of arguments. If the block takes no arguments, the selector is value. If it takes one argument, the selector is value:. If it takes two arguments, the selector is value:With:, for three the selector is value:With:With:, and for more the selector is just extended by enough With:’s to match the number of block arguments.

Block evaluation has two phases. In the first phase, a block object is created because the block is evaluated (e.g., it is used as an argument to a message send). The block is cloned and given a pointer to the activation record for its lexically enclosing scope, the current activation record. In the second phase, the block’s method is evaluated as a result of sending the block the appropriate variant of the value message. The block method is then cloned, the argument slots of the clone are filled in, the anonymous parent slot of the clone is initialized using the scope pointer determined in phase one, and, finally, the block’s code is executed.

It is an error to evaluate a block method after the activation record for its lexically enclosing scope has returned. Such a block is called a non-lifo block because returning from it would violate the last-in, first-out semantics of activation object invocation.

This restriction is made primarily to allow activation records to be allocated from a stack. A future release of Self may relax this restriction, at least for blocks that do not access variables in enclosing scopes.

Returns¶

A return is denoted by preceding an expression by the ‘^’ operator. A return causes the value of the given expression to be returned as the result of evaluating the method or block. Only the last expression in an object may be a return.

The presence or absence of the ‘^’ operator does not effect the behavior of ordinary methods, since an ordinary method always returns the value of its final expression anyway. In a block, however, a return causes control to be returned from the ordinary method containing that block, immediately terminating that method’s activation, the block’s activation, and all activations in between. Such a return is called a non-local return, since it may “return through” a number of activations. The result of the ordinary method’s evaluation is the value returned by the non-local return. For example, in the following method:

assertPositive: x = ( x > 0 ifTrue: [ ^ ’ok’ ]. error: ’non-positive x’ )

the error: message will not be sent if x is positive because the non-local return of ‘ok’ causes the assertPositive: method to return immediately.

Construction of object literals¶

Object literals are constructed during parsing—the parser converts objects in textual form into real Self objects. An object literal is constructed as follows:

- First, the slot initializers of every slot are evaluated from left to right. If a slot initializer contains another object literal, this literal is constructed before the initializer containing it is evaluated. If the initializer is an expression, it is evaluated in the context of the lobby.

- Second, the object is created, and its slots are initialized with the results of the evaluations performed in the first step.

Slot initializers are not evaluated in the lexical context, since none exists at parse time; they are evaluated in the context of an object known as the lobby. That is, the initializers are evaluated as if they were the code of a method in a slot of the lobby. This two-phase object construction process implies that slot initializers may not refer to any other slots within the constructed object (as with Scheme’s let* and letrec forms) and, more generally, that a slot initializer may not refer to any textually enclosing object literal.

Slot descriptors¶

An object can have any number of slots. Slots can contain data (data slots) or methods. Some slots have special roles: argument slots are filled in with the actual arguments during a message send (§2.3.3), and parent slots specify inheritance relationships (§2.3.8).

A slot descriptor consists of an optional privacy specification, followed by the slot name and an optional initializer.

Read-only slots¶

A slot name followed by an equals sign (‘=’) and an expression represents a read-only slot initialized to the result of evaluating the expression in the root context.

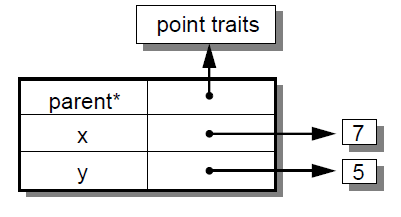

For example, a constant point might be defined as:

( | parent* = traits point. x = 3 + 4. y = 5. | )

The resulting point contains three initialized read-only slots:

Read/write slots¶

There is no separate assignment operation in Self. Instead, assignments to data slots are message sends that invoke the assignment primitive. For example, a data slot x is assignable if and only if there is a slot in the same object with the same name appended with a colon (in this case, x:), containing the assignment primitive. Therefore, assigning 17 to slot x consists of sending the message x: 17. Since this is indistinguishable from a message send that invokes a method, clients do not need to know if x and x: comprise data slot accesses or method invocations.

An identifier followed by a left arrow (the characters ‘<’ and ‘-’ concatenated to form ‘<-’) and an expression represents an initialized read/write variable (assignable data slot). The object will contain both a data slot of that name and a corresponding assignment slot whose name is obtained by appending a colon to the data slot name. The initializing expression is evaluated in the root context and the result stored into the data slot at parse time.

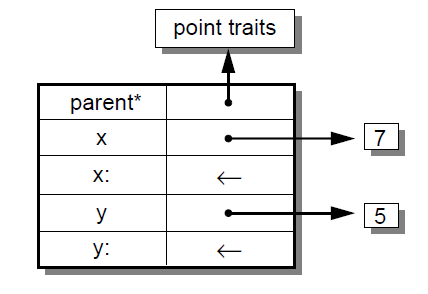

For example, an initialized mutable point might be defined as:

( | parent* = traits point. x <- 3 + 4. y <- 5. | )

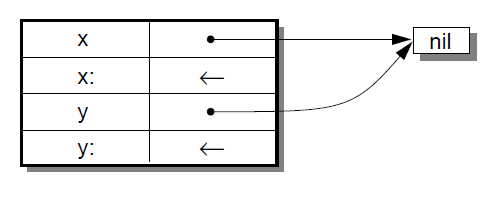

producing an object with two data slots (xand y) and two assignment slots (x:and y:) containing the assignment primitive (depicted with ←): [4]

An identifier by itself specifies an assignable data slot initialized to nil . [5] Thus, the slot declaration x is a shorthand notation for x <- nil.

For example, a simple mutable point might be defined as:

( | x. y. | )

producing:

Slots containing methods¶

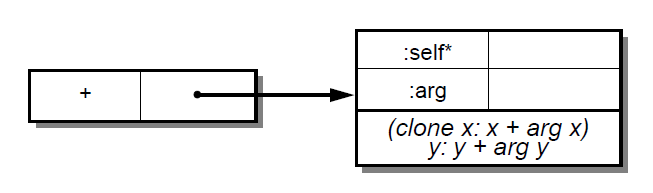

If the initializing expression is an object literal with code, that object is stored into the slot without evaluating the code. This allows a slot to be initialized to a method by storing the method itself, rather than its result, in the slot. [6] Methods may only be stored in read-only slots. A method automatically receives a parent argument slot named self. For example, a point addition method can be written as:

( | + = ( | :arg | (clone x: x + arg x) y: y + arg y ). | )

producing:

A slot name beginning with a colon indicates an argument slot. The prefixed colon is not part of the slot name and is ignored when matching the name against a message. Argument slots are always read-only, and no initializer may be specified for them. As a syntactic convenience, the argument name may also be written immediately after the slot name (without the prefixed colon), thereby implicitly declaring the argument slot. Thus, the following yields exactly the same object as above:

( | + arg = ( (clone x: x + arg x) y: y + arg y ). | )

The + slot above is a binary slot (§2.3.2), taking one argument and having a name that consists of operator symbols. Slots like x or y in a point object are unary slots (§2.3.1), which take no arguments and have simple identifiers for names. In addition, there are keyword slots (§2.3.3), which handle messages that require one or more arguments. A keyword slot name is a sequence of identifiers, each followed by a colon.

The arguments in keyword methods are handled analogously to those in binary methods: each colon-terminated identifier in a keyword slot name requires a corresponding argument slot in the keyword method object, and the argument slots may be specified either all in the method or all interspersed with the selector parts.

For example:

( | ifTrue: False: = ( | :trueBlock. :falseBlock | trueBlock value ). | )

and

( | ifTrue: trueBlock False: falseBlock = ( trueBlock value ). | )

produce identical objects.

Parent slots¶

A unary slot name followed by an asterisk denotes a parent slot. The trailing asterisk is not part of the slot name and is ignored when matching the name against a message. Except for their special meaning during the message lookup process (§2.3.8), parent slots are exactly like normal unary slots; in particular, they may be assignable, allowing dynamic inheritance. Argument slots cannot be parent slots.

Annotations¶

In order to provide extra information for the programming environment, Self supports annotations on either whole objects or individual slots. Although any object can be an annotation, the Self syntax only supports the textual definition of string annotations. In order to annotate an object, use this syntax:

( | {} = ’this object has one slot’ snort = 17. | ) }

In order to annotate a group of slots, surround them with braces and insert the annotation after the opening brace:

( | { ’Category: accessing’ getOne = (...). getAnother = (...). } anUnannotatedSlot. | )

Annotations may nest; if so the Virtual Machine concatenates the annotations strings and inserts a separator character (16r7f). [7]

Expressions¶

Expressions in Self are messages sent to some object, the receiver. Self message syntax is similar to Smalltalk’s. Self provides three basic kinds of messages: unary messages, binary messages, and keyword messages. Each has its own syntax, associativity, and precedence. Each type of message can be sent either to an explicit or implicit receiver.

Productions: [8]

| expression | → | constant | unary-message | binary-message | keyword-message | ‘(’ expression ‘)’ |

| constant | → | self | number | string | object |

| unary-message | → | receiver unary-send | resend ‘.’ unary-send |

| unary-send | → | identifier |

| binary-message | → | receiver binary-send | resend ‘.’ binary-send |

| binary-send | → | operator expression |

| keyword-message | → | receiver keyword-send | resend ‘.’ keyword-send |

| keyword-send | → | small-keyword expression { cap-keyword expression } |

| receiver | → | [ expression ] |

| resend | → | resend | identifier |

The table below summarizes Self’s message syntax rules:

| MESSAGE | ARGUMENTS | PRECEDENCE | ASSOCIATIVITY | SYNTAX |

| Unary | 0 | highest | none | [receiver] identifier |

| binary | 1 | medium | none or left-to-right* | [receiver] operator expression |

| keyword | ≥ 1 | lowest | right-to-left | [receiver] small-keyword expression { cap-keyword expression } |

* Heterogeneous binary messages have no associativity; homogeneous binary messages associate left-to-right.

Parentheses can be used to explicitly specify order of evaluation.

Unary messages¶

A unary message does not specify any arguments. It is written as an identifier following the receiver.

Examples of unary messages sent to explicit receivers:

17 print 5 factorial

Associativity. Unary messages compose from left to right. An expression to print 5 factorial, for example, is written:

5 factorial print

and interpreted as:

(5 factorial) print

Precedence. Unary messages have higher precedence than binary messages and keyword messages.

Binary messages¶

A binary message has a receiver and a single argument, separated by a binary operator. Examples of binary messages:

3 + 4 7 <-> 8

Associativity. Binary messages have no associativity, except between identical operators (which associate from left to right). For example,

3 + 4 + 7

is interpreted as

(3 + 4) + 7

But

3 + 4 * 7

is illegal: the associativity must be made explicit by writing either

(3 + 4) * 7 or 3 + (4 * 7).

Precedence. The precedence of binary messages is lower than unary messages but higher than keyword messages. All binary messages have the same precedence. For example,

3 factorial + pi sine

is interpreted as

(3 factorial) + (pi sine)

Keyword messages¶

A keyword message has a receiver and one or more arguments. It is written as a receiver followed by a sequence of one or more keyword-argument pairs. The first keyword must begin with a lower case letter or underscore (‘_’); subsequent keywords must be capitalized. An initial underscore denotes that the operation is a primitive. A keyword message consists of the longest possible sequence of such keyword-argument pairs; the message selector is the concatenation of the keywords forming the message. Message selectors beginning with an underscore are reserved for primitives (§2.3.7).

Example:

5 min: 4 Max: 7

is the single message min:Max: sent to 5 with arguments 4 and 7, whereas

5 min: 4 max: 7

involves two messages: first the message max:sent to 4 and taking 7 as its argument, and then the message min: sent to 5, taking the result of (4 max: 7) as its argument.

Associativity. Keyword messages associate from right to left, so

5 min: 6 min: 7 Max: 8 Max: 9 min: 10 Max: 11

is interpreted as

5 min: (6 min: 7 Max: 8 Max: (9 min: 10 Max: 11))

The association order and capitalization requirements are intended to reduce the number of parentheses necessary in Self code. For example, taking the minimum of two slots mand nand storing the result into a data slot i may be written as

i: m min: n

Precedence. Keyword messages have the lowest precedence. For example,

i: 5 factorial + pi sine

is interpreted as

i: ((5 factorial) + (pi sine))

Implicit-receiver messages¶

Unary, binary, and keyword messages are frequently written without an explicit receiver. Such messages use the current receiver (self) as the implied receiver. The method lookup, however, begins at the current activation object rather than the current receiver (see §2.1.4 for details on activation objects). Thus, a message sent explicitly to self is not equivalent to an implicit-receiver send because the former won’t search local slots before searching the receiver. Explicitly sending messages to self is considered bad style.

Examples:

factorial (implicit-receiver unary message) + 3 (implicit-receiver binary message) max: 5 (implicit-receiver keyword message) 1 + power: 3 (parsed as 1 + (power: 3))

Accesses to slots of the receiver (local or inherited) are also achieved by implicit message sends to self. For an assignable data slot named t, the message t returns the contents, and t: 17 puts 17 into the slot.

Resending messages¶

A resend allows an overridding method to invoke the overridden method. Directed resends allow ambiguities among overridden methods to be resolved by constraining the lookup to search a single parent slot. Both resends and directed resends may change the name of the message being sent from the name of the current method, and may pass different arguments than the arguments passed to the current method. The receiver of a resend or a directed resend must be the implicit receiver.

Intuitively, resend is similar to Smalltalk’s supersend and CLOS’ call-next-method.

A resend is written as an implicit-receiver message with the reserved word resend, a period, and the message name. No whitespace may separate resend, the period, and the message name.

Examples:

resend.display resend.+ 5 resend.min: 17 Max: 23

A directed resend constrains the resend through a specified parent. It is written similar to a normal resend, but replaces resend with the name of the parent slot through which the resend is directed.

Examples:

listParent.height intParent.min: 17 Max: 23

Only implicit-receiver messages may be delegated via a resend or a directed resend. [9]

Message lookup semantics¶

This section describes the semantics of message lookups in Self. In addition to an informal textual description, the lookup semantics are presented in pseudo-code using the following notation:

s.name The name of slot s. s.contents The object contained in slot s. s.isParent True iff s is a parent slot. {s ε obj | pred(s)} The set of all slots of object obj that satisfy predicate pred. | S | The cardinality of set S.

The message sending semantics are decomposed into the following functions:

send(rec, sel, args) The message send function (§2.3.7). lookup(obj, rec, sel, V) The lookup algorithm (§2.3.8). undirected_resend(...) The undirected message resend function (§2.3.9). directed_resend(...) The directed message resend function (§2.3.9). eval(rec, M, args) The slot evaluation function as described informally throughout §2.1.

Message send¶

There are two kinds of message sends: a primitive send has a selector beginning with an underscore (‘_’) and calls the corresponding primitive operation. Primitives are predefined functions provided by the implementation. A normal send does a lookup to obtain the target slot; if the lookup was successful, the slot is subsequently evaluated. If the slot contains a data object, then the data object is simply returned. If the slot contains the assignment primitive, the argument of the message is stored in the corresponding data slot. Finally, if the slot contains a method, an activation is created and run as described in §2.1.6.

If the lookup fails, the lookup error is handled in an implementation-defined manner; typically, a message indicating the type of error is sent to the object which could not handle the message.

The function send(rec, sel, args) is defined as follows:

- Input:

- Output:

Algorithm

if begins_with_underscore(sel) then invoke_primitive(rec, sel, args) “primitive call” else M ← lookup(rec, sel, Ø) “do the lookup” case | M | = 0: error: message not understood | M | = 1: res ← eval(rec, M, args) “see §2.1” | M | > 1: error: ambiguous message send end end return res

The lookup algorithm¶

The lookup algorithm recursively traverses the inheritance graph, which can be an arbitrary graph (including cyclic graphs). No object is searched twice along any single path. The search begins in the object itself and then continues to search every parent. Parent slots are not evaluated during the lookup. That is, if a parent slot contains an object with code, the code will not be executed; the object will merely be searched for matching slots.

The function lookup(obj, sel, V) is defined as follows:

- Input:

- Output:

Algorithm:

if obj ε V then M ← Ø “cycle detection” else M ← {s ε obj | s.name = sel} “try local slots” if M = Ø then M ← parent_lookup(obj, sel, V) end “try parent slots” end return M

Where parent_lookup(obj, sel, V) is defined as follows:

P ← {s ε obj | s.isParent} “all parents” M ← υ lookup(s.contents, sel, V υ {obj}) “recursively search parents” sεP return M

Undirected Resend¶

An undirected resend ignores the sending method holder (the object containing the currently running method) and continues with its parents.

The function undirected_resend(rec, smh, sel, args) is defined as follows:

- Input:

- Output:

Algorithm:

M ← parent_lookup(smh, sel, Ø) “do the lookup” case | M | = 0: error: message not understood | M | = 1: res ← eval(rec, M, args) “see §2.1” | M | > 1: error: ambiguous message send end return res

Directed Resend¶

A directed resend looks only in one slot in the sending method holder.

The function directed_resend(rec, smh, del, sel, args) is defined as follows:

- Input:

- Output:

Algorithm:

D ← {s ε smh | s.name = del} “find delegatee” if | D | = 0 then error: missing delegatee “one or none” M ← lookup(smh.del, sel, Ø) “do the lookup” case | M | = 0: error: message not understood | M | = 1: res ← eval(rec, M, args) “see §2.1” | M | > 1: error: ambiguous message send end return res

Lexical elements¶

This chapter describes the lexical structure of Self programs—how sequences of characters in Self source code are grouped into lexical tokens. In contrast to syntactic elements described by productions in the rest of this document, the elements of lexical EBNF productions may not be separated by whitespace, i.e. there may not be whitespace within a lexical token. Tokens are formed from the longest sequence of characters possible. Whitespace may separate any two tokens and must separate tokens that would be treated as one token otherwise.

Character set¶

Self programs are written using the following characters:

- Letters. The fifty-two upper and lower case letters: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

- Digits. The ten numeric digits: 0123456789

- Whitespace. The formatting characters: space, horizontal tab (ASCII HT), newline (NL), carriage return (CR), vertical tab (VT), backspace (BS), and form feed (FF). (Comments are also treated as whitespace.)

- Graphic characters. The 32 non-alphanumeric characters: !@#$%^&*()_-+=|\~‘{}[]:;”’<>,.?/

Identifiers¶

An identifier is a sequence of letters, digits, and underscores (‘_’) beginning with a lowercase letter or an underscore. Case is significant: apoint is not the same as aPoint.

Productions:

small-letter → ‘a’ | ‘b’ | ... | ‘z’ cap-letter → ‘A’ | ‘B’ | ... | ‘Z’ letter → small-letter | cap-letter identifier → (small-letter | ‘_’) {letter | digit | ‘_’}

Examples: i _IntAdd cloud9 m a_point

The two identifiers self and resend are reserved. Identifiers beginning with underscores are reserved for primitives.

Keywords¶

Keywords are used as slot names and as message names. They consist of an identifier or a capitalized identifier followed by a colon (‘:’).

Productions:

small-keyword → identifier ‘:’ cap-keyword → cap-letter {letter | digit | ‘_’} ‘:’

Examples: at: Put: _IntAdd:

Arguments¶

A colon followed by an identifier denotes an argument slot name.

Productions:

arg-name → ‘:’ identifier

Example: :name

Operators¶

An operator consists of a sequence of one or more of the following characters:

! @ # $ % ^ & * - + = ~ / ? < > , ; | ‘ \

Two sequences are reserved and are not operators:

| ^

Productions:

op-char → ‘!’ | ‘@’ | ‘#’ | ‘$’ | ‘%’ | ‘^’ | ‘&’ | ‘*’ | ‘-’ | ‘+’ | ‘=’ | ‘~’ | ‘/’ | ‘?’ |‘<’ | ‘>’ | ‘,’ | ‘;’ | ‘|’ | ‘‘’ | ‘’ operator → op-char {op-char}

Examples: + - && || <-> % # @ ^

Numbers¶

Integer literals are written as a sequence of digits, optionally prefixed with a minus sign and/or a base. [10] No whitespace is allowed between a minus sign and the digit sequence. [11] Real constants may be either written in fixed-point or exponential form.

Integers may be written using bases from 2 to 36. For bases greater than ten, the characters ‘a’ through ‘z’ (case insensitive) represent digit values 10 through 35. The default base is decimal. A non-decimal number is prefixed by its base value, specified as a decimal number followed by either ‘r’ or ‘R’.

Real numbers may be written in decimal only. The exponent of a floating-point format number indicates multiplication of the mantissa by 10 raised to the exponent power; i.e.,

nnnnEddd = nnnn × 10 ddd

A number with a digit that is not appropriate for the base will cause a lexical error, as will an integer constant that is too large to be represented. If the absolute value of a real constant is too large or too small to be represented, the value of the constant will be ± infinity or zero, respectively.

Productions:

number → [ ‘-’ ] (integer | real) integer → [base] general-digit {general-digit} real → fixed-point | float fixed-point → decimal ‘.’ decimal float → decimal [ ‘.’ decimal ] (‘e’ | ‘E’) [ ‘+’ | ‘-’ ] decimal general-digit → digit | letter decimal → digit {digit} base → decimal (‘r’ | ‘R’)

Examples: 123 16r27fe 1272.34e+15 1e10

Strings¶

String constants are enclosed in single quotes (‘’’). With the exception of single quotes and escape sequences introduced by a backslash (‘\’), all characters (including formatting characters like newline and carriage return) lying between the delimiting single quotes are included in the string. [12]

To allow single quotes to appear in a string and to allow non-printing control characters in a string to be indicated more visibly, Self provides C-like escape sequences:

\t tab \b backspace \n newline \f form feed \r carriage return \v vertical tab \a alert (bell) \0 null character \ \ backslash \’ single quote \” double quote \? question mark

A backslash followed by an ‘x’, ‘d’, or ‘o’ specifies the character with the corresponding numeric encoding in the ASCII character set:

\xnn hexadecimal escape \dnnn decimal escape \onnn octal escape

There must be exactly two hexadecimal digits for hexadecimal character escapes, and exactly three digits for decimal and octal character escapes. Illegal hexadecimal, decimal, and octal numbers, as well as character escapes specifying ASCII values greater than 255 will cause a lexical error.

For example, the following characters all denote the carriage return character (ASCII code 13):

\r \x0d \d013 \o015

A long string may be broken into multiple lines by preceding each newline with a backslash. Such escaped newlines are ignored during formation of the string constant.

A backslash followed by any other character than those listed above will cause a lexical error.

Productions:

string → ‘’’ { normal-char | escape-char } ‘’’ normal-char → any character except ‘\’ and ‘’’ escape-char → ‘\t’ | ‘\b’ | ‘\n’ | ‘\f’ | ‘\r’ | ‘\v’ | ‘\a’ | ‘\0’ | ‘\ \’ | ‘\’’ | ‘\”’ | ‘\?’ | numeric-escape numeric-escape → ‘\x’ general-digit general-digit | ( ‘\d’ | ‘\o’ ) digit digit digit

Comments¶

Comments are delimited by double quotes (‘”’). Double quotes may not themselves be embedded in the body of a comment. All characters (including formatting characters like newline and carriage return) are part of the body of a comment.

Productions:

comment → ‘”’ { comment-char } ‘”’ comment-char → any character except ‘”’

Example: “this is a comment”

Footnotes

| [1] | If you wish to use the empty vertical bar notation to create an empty object, note that the parser currently requires a space between the vertical bars. |

| [2] | But in that case make sure you put a space after the period, otherwise you will get an obscure error message from the parser. |

| [3] | All block objects have the same parent, an object containing the shared behavior for blocks |

| [4] | In the user interface a read/write slot is depicted as a single slot with a colon labelling the button used to access the value of the slot; the assignment slot is not shown, to save screen space. In contrast, a read-only slot has an equals sign on the button. |

| [5] | Nil is a predefined object provided by the implementation. It is intended to indicate “not a useful object.” |

| [6] | Although a block may be assigned to a slot at any time, it is often not useful to do so: evaluating the slot may result in an error because the activation record for the block’s lexically enclosing scope will have returned; see §2.1.7. |

| [7] | The current programming environment expects a slot annotation to start with one of a number of keywords, including “Category: ”, “Comment: ”, and “ModuleInfo:”. See the programming environment manual for more details. |

| [8] | In order to simplify the presentation, this grammar is ambiguous; precedence and associativity rules are used to resolve the ambiguities. |

| [9] | General delegation for explicit receiver messages is supported through primitives in the implementation (see Appendix 9.8). |

| [10] | Unlike Smalltalk, integer literals are limited in range to smallInts. |

| [11] | In situations where parsing the minus sign as part of the number would cause a parse error (for example, in the expression a-1), the minus is interpreted as a binary message (a - 1). |

| [12] | When typing strings in, the graphical user interface accepts multi-line strings, but the character-based read-evalprint loop does not. |

| [13] | In order to simplify the presentation, this grammar is ambiguous; precedence and associativity rules are used to resolve the ambiguities. |